-

Search this site

-

Stats

- 9,017 hits

-

Archive

-

Posts since May 2021

- A walk up to the Ramsden Clough rifle range March 6, 2023

- Favourite Venues October 12, 2022

- New Mill MVC go to London (2) August 6, 2022

- New Mill MVC go to London August 4, 2022

- Rita Tushingham – shares our repertoire June 26, 2022

- New Mill Publishes in Learned Journal May 25, 2022

- Upperthong – book now to avoid disappointment April 27, 2022

- Dvorak – New World Symphony – Going Home March 29, 2022

- New Mill’s 2022 concert schedule March 28, 2022

- It’s not a throat lozenge February 9, 2022

Tag Archives: choral music

Swinglo joins The Northern Concert Choir to sing Faure\’s Requiem and Vivaldi\’s Gloria

|

| Laurel and Hardy tribute, Scarborough |

So I\’m Dave Walker, baritone, (the one on the left) from New Mill MVC and I have volunteered to help Viv out with content on Facebook. I enjoy writing so it\’s not much of a chore. The one on the right is Clive Hetherington, bass, another NMMVC member who is singing with The Northern Choir.

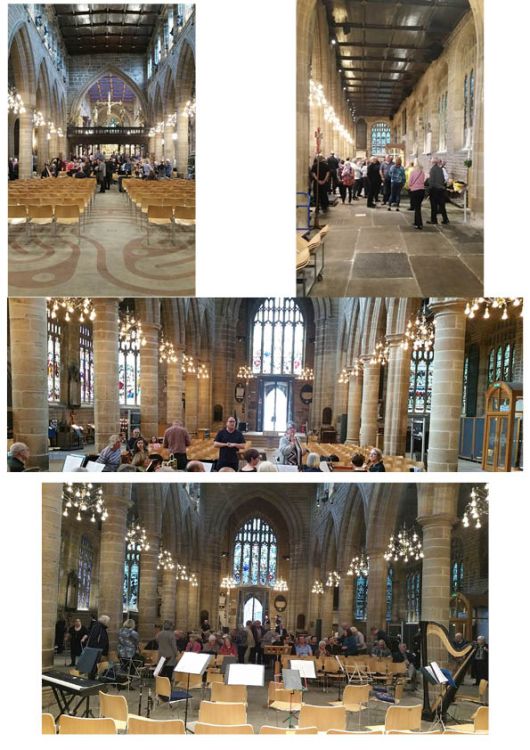

A cold wet Sunday afternoon in the back streets of Skelmanthorpe. Possibly not your ideal landscape for Faure and Vivaldi rehearsals, but it is what it is. I cannot remember where I first saw this venture advertised. It\’s the brainchild of Jane Hobson and Dan Timmins, both accomplished singers and choir musical directors. I\’ve been aware of a personal need to sing choral pieces and this is a chance. Well over one hundred have signed up. A bit of a squeeze for rehearsals at Skelmanthorpe Methodists, but probably okay for our two concerts at Sheffield and Wakefield Cathedrals. Faure\’s Requiem and Vivaldi\’s Gloria are the planned performances. Two thirds or so will then move on to Malta for three further concerts.

The pieces are in latin and to say I don\’t get latin is an understatement. I was so bad at school they didn\’t waste their money on an \’O\’ level. There are translations, but the Requiem can be a bit dark. So the words are notes to hit. Vocalising – a recent article in the Times described a number of choirs who simply turn up and sing, with a conductor, but it seems to be primarily about enjoying making sounds and pitch could be secondary. Maybe choral music in latin is well-organised vocalisation. I\’m happy with that.

Homework is expected and rehearsal aids are plentiful and helpful.

Parking is not a problem around the chapel, but I wonder what the residents think?

Dave Talboys is practising beer drinking, watched by Chris. Both are from Thurstonland Community Choir. Clive\’s attention has wandered.

I\’m with David Millward (also sings with Holmfirth Choral), tenor, and Alan Brierley with two black eyes, musical director (also with the U3A choir).

Viv did wonder whether Facebook could make a feature of all the choirs represented in this venture. I wondered if some pics like the above might do the same with some text?

Choral music and Roderick Williams OBE (2)

Roderick Williams refers to this podcast as singing for solidarity. Singing with others for joy, to summon communities and to change the world. Roger Scruton tells us that singing with others for a common purpose is a national and european tradition, whether it be in a choir, at a football match or as part of a church service. He goes on to say that our place, from nationhood to where we are personally, is commonly expressed in singing. Identity, where we belong, music and singing all go together.

Professor Stephen Clift talks of singing as a basic part of human nature, common to all of our cultures and all historic periods. It is non-elitist and when in a group takes it to a level of harmony with others that we do not achieve in everyday life.

Oskar Cox Jensen, historian and writer, expanding on the nationhood theme, describes how God Save the King originated as Jacobite support for the pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie. It disappeared for 70 years and re-emerged as a folksong, popular in the music halls and eventually sung regularly at the end of theatre performances. An adopted National Anthem. It was associated with gang violence in Edinburgh in 1792 when Walter Scott fell out with Irish students and it has a number of different versions, not always complimentary to the monarchy, comparable to football team anthems. Hence music and singing together as expressions of dissent and revolution. Supporters of W. B. Albion agreed that intimidating the opposition was the purpose behind some of their singing.

Anna Redding, during the Women\’s Peace Camp days of Greenham Common, recalls how singing together round the campfire helped them through some of their primitive living conditions and, when they really got going, it was like a collective ecstasy.

The Birmingham Clarion Singers, according to Annie Banham and Jane Scott, began in 1940 when a doctor returned from the Spanish Civil War. Songs of fighting and learning the lessons of the past – the chartists of the 1830s. It is about working class singing – popular protest, a desire for representation.

Workplaces encourage choirs and singing. Alexandria Winn is proud to be part of a Lawyer firm choir in Birmingham. Different floors and departments, not normally known to each other, come together and make a singing community.

In the previous blog we learned about the personal gain of enjoying and being inspired by singing and by the relationships we nurture as a result of the shared interest or passion. Singing is also good for your health and gives you a sense of achievement – clic on link for Chris Rowbury\’s post Reasons for Singing. Today contains examples of why people come together and sing – protest, sense of community, loyalty to place and football team or simply that sense of sharing in something which is much greater than the sum of its parts.

It\’s not for everyone says Stephen Clift – we cannot generalise. Nearly everyone then.

Lent – can you give up music?

My pal Greg has given up alcohol for Lent and is still managing. I have stopped being grumpy, or that was the intention. Trevor Cox tried to give up music – listen to his podcast.

What might be the ups and downs of not having music in our lives?

A strong benefit is not being influenced by background music in pubs, restaurants and clothing shops. Professor Charles Spence describes how, for example, so-called background music (French, German) in a restaurant influences our food and wine choices. Similarly, fast and slow tempo music can speed us up when they are busy or slow us down when they are slack. Apparently we have no recollection of this as we leave.

There may be costs such as not appreciating or even getting the point of TV and film drama. Composer Debbie Wiseman tells us we can often get the drift of things purely with the music. And not the Hollywood variety – better music that creates mood and emotion – space to take in what is not being shown on the screen. If you have the habit of watching these programmes with others, then that social time would also suffer.

Another cost is the lack of brain arousal. Switched on at a low level. According to Dr. Victoria Williamson it would be quicker to list what brain structures don\’t light up when listening to music. Even basic reward centres that deal with our survival as a species – like the need for food, water and sex. These centres lie between memory and emotion, so it\’s all quite a light bulb. We may need to seek substitutes – drugs, sex and rock\’n roll (no, I really mean chocolate).

There are medical connotations, not directly related to the absence of music, more a consequence of other factors. Anhedonia is a mental symptom when we are unable to enjoy what would normally turn us on. If, over a long time, we stop listening to our favourite music along with other things we normally take pleasure in, our friends and relatives might need to think about depression.

Amusia is the technical term for tone deafness. It effects 4% of the population from birth and can be a side effect of brain injury in later life. Again there is no pleasure in music. Tone deaf people cannot make sense of music and cannot recognise a familiar tune says Lauren Stewart. Sadly they can avoid normal everyday interactions involving music and can be social hermits.

Amusia is the technical term for tone deafness. It effects 4% of the population from birth and can be a side effect of brain injury in later life. Again there is no pleasure in music. Tone deaf people cannot make sense of music and cannot recognise a familiar tune says Lauren Stewart. Sadly they can avoid normal everyday interactions involving music and can be social hermits.

To summarise Trevor Cox\’s exploration of not having music in our lives, we lose the personal gain of enjoying and being inspired by something and also the relationships we nurture as a result of the shared interest or passion. This surely resonates with New Mill MVC, who gain from both simultaneously.

The question remains \’what is music?\’ Tom Service from the BBC talks about music as sound which we interpret as meaningful. Otherwise it is simply a sound. Take a baby crying – there is pitch, tempo and timbre with a large number of interpretations. There can\’t be many sounds that don\’t arouse personal meaning. According to composer Edgard Varese however we need to organise the quality and quantity of sounds before we would call it music.

If music is simply a meaningful sound, it would be rather hard to give it up for Lent. It\’s all around us. Easier if it were organised sound.

Choral Music and Roderick Williams OBE

Choral music in Great Britain 1

Roderick Williams OBE, with guests, talks about choral music. On the one hand he says there are over 40000 choirs ranging from pop to classical – on the other he wonders if singing in Britain will survive. There has never been a better time for new writing by composers for specific choirs as commissions. There are two very popular current choral recordings: (1) Tallis – Spem in Allium – (clic here for Utube) which features on the soundtrack of 50 Shades of Grey and (2) Mealor – Ubi Caritas – (clic here for Utube) from the Catherine and William wedding (Mealor wrote Wherever You Are for Military Wives).

Yet, Rod says, singing is on the decline. In a 1927 recording of Abide With Me from the Soccer Cup final, 92000 fans knew the words and music and just sang. A good proportion of the crowd today would not know the words. TV, Radio, Records, CDs and all the other ways of listening to music have expanded at the expense of personal singing. Weddings and funerals have less hymns and attendance at church generally is falling. If a singer is needed, he/she/them is brought in – just like New Mill.

In pre-industrial Britain, people sang at work – spinners, weavers, waggoners, farm labourers, sailors and so on. The musical rhythms fitted the work tasks and helped get the work done. This spilt into leisure, down the pub and in the music hall. When factory discipline came in, singing was banned and those that tried were fined. Some establishments even had no talking. Anyway the machines were very noisy, sidestepped by the lip-readers of the Dundee Jute Mills.

Class and snootiness have also had a role. Since the nineteenth century, voices of the ordinary people have been looked down upon by the gentry and those who would like to be gentry. Crude, unlettered and vulgar are some of the words used. An attitude that transferred to education. Personal singing down the pub and in the music hall was raw and edgy and frowned upon.

Rod introduces two organisations that simply sing – Natural Voice Network and the London Bulgarian Choir. They encourage people, whether they think they can sing or not, to connect with others and share the joy of making musical sounds together. The London choir, with many English speakers, cannot understand the words, so it\’s all about making great sound. Like us or me singing in latin – maybe not the great sound bit. Ged is conducting us in Ilkley for just this sort of piece.